Half a century after mercury contamination near Grassy Narrows First Nation, the poisoning continues to have deadly consequences — especially for youth.

Azraya Ackabee-Kokopenace wanted help. That’s all anyone knows for sure.

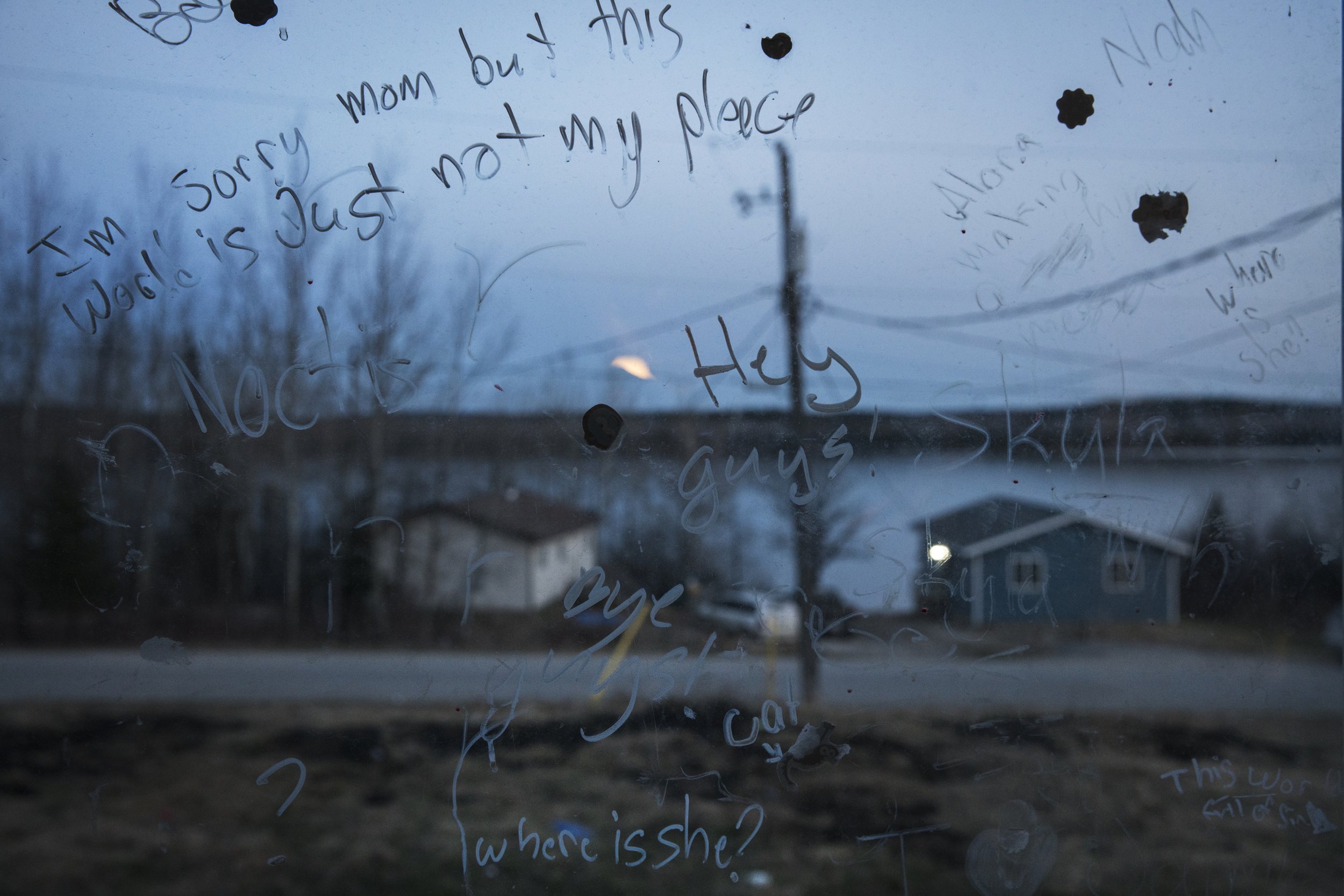

The girl with the bright smile had just turned 14 when she left her family in Grassy Narrows First Nation in northwestern Ontario last spring in search of someone — or something — to ease her overwhelming grief.

On April 17, 2016, Azraya was found dead in a wooded area just across the road from Lake of the Woods District Hospital in Kenora, Ont., 90 kilometres south of Grassy Narrows. More than a year later, no one seems to know how she got there.

Azraya’s last interactions were with Ontario Provincial Police in Kenora and possibly staff at the hospital, where police say they dropped her off two days earlier. Police and hospital officials refuse to answer questions about what happened that night.

This past April, on the first anniversary of her death, Azraya’s parents attended a vigil and wept quietly by the tree where their daughter’s body was discovered. Candles flickered in the pink evening light, perfectly reflected in the still lake nearby. Anishinaabe grandmothers sang a traditional mourning song, their drums echoing the rhythm of a heartbeat in the damp spring air.

Azraya’s parents, Christa Ackabee and Marlin Kokopenace, had arrived with a small group that marched through the streets of Kenora in the hope that the anniversary would add weight to their call for answers. Some of the people in the group carried homemade signs saying “Justice for Azraya.” They slowed traffic, demanding a coroner’s inquest.

“We deserve to know the truth,” said Azraya’s friend Kyra Sinclair, who is 15. “It may not bring her back, but it’s our only way to cope with everyday life.”

Solving the mystery of Azraya’s death has special urgency for young people in Grassy Narrows, who see her final days as the embodiment of an intergenerational tragedy unique to their community.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, industrial pollution contaminated the water in Grassy Narrows (Asubpeeschoseewagong) with mercury, making it one of Canada’s worst environmental disasters. The contamination in this community of about 1,000 residents has affected three generations.

Ninety per cent of the population in Grassy Narrows experiences symptoms of mercury poisoning, which include neurological problems ranging from numbness in fingers and toes to seizures and cognitive delays, according to a recent study by mercury specialists. Then there’s the psychological stress of seeing your friends and family stricken with these problems.

But health services are limited to a small nursing station, and mental health counselling on the reserve is nearly non-existent.

Azraya’s friends believe her death was tied to her despair over the loss of her older brother Calvin, who died from mercury poisoning in 2014.

“Knowing how Calvin died, we could all be dying. We probably are, already, and we don’t know what’s going to happen because nobody is helping,” said Chayna Loon, one of Azraya’s cousins. “Knowing that [Calvin] went through that, it makes everybody sad. Azraya took it the worst.”

Friends and family believe it was Azraya’s quest for help in dealing with her grief that led her to Kenora.

Her death has become an emblem of the social devastation that followed the environmental destruction at Grassy Narrows, leaving many to wonder: If a child’s plea for help can go unanswered and the details of her death can remain hidden from her family, what hope is there of healing?

II. A legacy of devastation

During the 1960s and early ‘70s, the chemical plant at the Reed Paper mill in Dryden, Ont., which is upstream of Grassy Narrows, dumped 9,000 kilograms of mercury into the English-Wabigoon River. The fish in the river were full of poison, and the people from Grassy Narrows, who relied on the fish as a staple in their diet, were full of it, too.

Once ingested, mercury never goes away. It “bioaccumulates,” meaning it passes from one generation to the next, from mother to child, through the placenta.

Sixty-five-year-old Steve Fobister is among the hardest hit by the mercury poisoning in Grassy Narrows. A former chief, skilled hunter and devoted advocate for his community, he now has difficulty standing and swallowing. He leans heavily on a walker to shuffle through the tiny bungalow he shares with his daughter and her children. Even talking is a chore. It often requires him to hold his lower jaw with his thumb to reduce the shaking long enough to form words.

Fobister receives $250 a month, the lowest amount granted through the Mercury Disability Board. The payment “doesn’t even meet my nutritional needs,” said Fobister. “I can’t afford anything that would give me some level of comfort. I suffer every day.”

The disability board was established in 1986 as part of a court settlement with Ontario and Canada and the two paper companies involved in the contamination. Neither the companies, the governments nor the disability board has ever admitted that anyone at Grassy Narrows has been poisoned — only that some people experience symptoms of Minamata disease.

The disease is named for the Japanese town where more than 100 people died after eating fish contaminated with mercury released into a lake by a chemical plant in the 1950s.

Japanese scientists have been studying people at Grassy Narrows and neighbouring Wabaseemoong (Whitedog) First Nation for decades, and in 2014 urged the federal government to provide care and financial support to every resident in the two communities affected by mercury.

The federal government has not heeded that call. Steve Fobister is among the select few who have received any compensation at all; Azraya’s brother Calvin also got some money before he died. Nearly 75 per cent of the claims sent to the board are denied, according to a 2014 report from the board’s chair.

The criteria for compensation was established as part of the court settlement in 1985 and remains unchanged, despite three decades of research by the Japanese scientists.

“I feel like we have not been able to accommodate the people that are sick,” said Fobister. “What is there for the people that are crippled with mercury symptoms? There’s nothing.”

It’s the youngsters Fobister worries about the most. Two of his grandchildren, Darwin and Catherine, are “severely” affected by symptoms associated with mercury poisoning. Darwin has difficulty with his balance, and often has the sensation that he’s going to fall forward. He also has problems with memory and concentration and suffers from extreme headaches.

“They’re never going to grow up normal,” Fobister said. “They have to go to appointments in Winnipeg with a neurologist just about every month. We struggle to make those appointments. There is no help. Medical services only cover a fraction of the travel.”

After decades of delay and mounting pressure from First Nations and environmental groups, the Ontario government announced in June that it would spend $85 million to clean up the mercury in the English-Wabigoon River. But Steve Fobister said the recent focus on remediating the river does not address the lingering issue of health care.

“I kind of resent the fact they’re going to spend money to do a cleanup. Everyone seems to ignore the ailments [associated with] the mercury problems.

“I saw one kid that died in agony not so long ago. They said that he had neurological problems and he died in a very sad way,” Fobister said. “We seem to have forgotten that. We seem to be following the money trail now.”

III. ‘It’s getting worse for us’

For people at Grassy Narrows, Azraya’s death raised an alarm about the mental health implications of the poisoning, and how it has affected community members who weren’t even born when the river was first contaminated.

After government scientists first confirmed the contamination in the 1970s, Ontario closed the commercial fishery in the English-Wabigoon River system. The lucrative fishing tourism industry near Grassy Narrows also crashed as a result of the poisoning, resulting in mass unemployment. All this came shortly after the community was relocated to a reserve, lured by the promise of better services, such as clean drinking water. To this date, there is still no safe tap water in most homes at Grassy Narrows.

Given these challenges, many people turned to alcohol to ease the pain of disability or idleness. Cramped homes became scarred by violence, with teens regularly the victims.

In 1983, a CBC documentary declared Grassy Narrows a community “on the verge of collapse.” It showed a picture of the Grade 8 class that year, and detailed the horrific fate of some of the students. One 15-year-old had been shot to death by her boyfriend; a 16-year-old classmate was charged with stabbing her boyfriend to death in self-defence; another 15-year-old had frozen to death walking home from a party.

A young, charismatic Steve Fobister appears in the documentary. He is healthy, handsome and energetic, as yet unmarred by the mercury — but making the same demands for compensation he does today.

“If the government says no, just like that, I’d fight like hell to demand that I have it my way, even if I have to lay my life on the line,” said the then-31-year-old Fobister.

There have been many battles — both public and private — during the decades of contamination at Grassy Narrows. Early protests led to the arrival of the Japanese researchers, who established the human health consequences of the contamination. More recent actions have included a blockade against logging that began in 2002 and continues to this day. Community members are pushing back against Ontario’s forestry regime because studies have shown that clear-cutting could release even more mercury into the environment.

Azraya’s death marked a new chapter in this decades-old tragedy. The youngest generation at Grassy Narrows has never known a time before the poisoning. They’ve never lived in a community where jobs are plentiful and disabilities rare. Few of them are familiar with a world beyond loss and pain and grief.

It’s a world Azraya went in search of — a place her friends still want to believe exists.

“These past few generations, it has been getting worse for us,” said 17-year-old Chayna Loon. “People look at us as drunks and addicts and that’s not our fault, because we’ve grown up in a really bad environment and because all we see is bad stuff. That’s all we believe in... bad stuff.”

When you talk to young people at Grassy Narrows, they tilt between despair and defiance. But their vulnerability is equalled by their resilience. They are frightened, but manage to be champions for kids even younger than themselves.

“I feel like the younger people are the ones who are going through a tougher time,” Chayna said. “I just want to be there for them. I want to help because nobody deserves to go through what’s going on.”

Despite his physical challenges, 20-year-old Darwin Fobister has worked to organize enjoyable diversions for the kids, like going swimming or to the movies.

“They want to see things. They want to explore and I just want to make sure they have activities, things they want. I don’t want them to turn towards the bad things, in bad places,” said Darwin, who heads the Grassy Narrows Youth Organization. “I want the youth to see there’s a greater thing they can turn to. I want them to see there’s a future coming towards them.”

Still, that future can be hard to see when your vision is clouded with tears. Kyra Sinclair imagines living her life away from the toxic past in Grassy Narrows. But to get there, she said she needs what Azraya was seeking: a way to deal with her grief.

The 15-year-old dropped out of school after Azraya’s death. She wants to go back so she can graduate and make a better life for herself and her baby daughter. But before that, she wants to get treatment for her alcohol dependency.

“I’m losing myself, I can feel it. It’s not the right way I want to be. I want to get the help I think I might need. I’m kind of struggling after losing Azraya,” she said. “It knocked me off my path.”

IV. Deaths in the family

Azraya’s friends and family say that finding answers about how she died will help get young people in Grassy Narrows back on track. So Darwin Fobister and other youngsters have become activists in seeking the truth.

Part of their challenge is understanding the role police played in Azraya’s final days.

“She was a nice, innocent, sweet girl. A sister that I loved and cared for,” said Azraya’s twin brother, Braeden Kokopenace, tears welling up in his eyes. “My sister was too young to go at this time and I believe police are part of it.”

When Azraya was struggling with her brother Calvin’s death, she asked her parents to put her in the care of a child welfare agency in Kenora so she could receive counselling. That’s when the trouble started. First, there was an altercation with a police officer outside the arena in Kenora, which was caught on video. In it, she is being held to the ground by the burly male officer, begging to go home. The OPP won’t answer questions about the incident.

It was a few weeks later that Azraya disappeared after police dropped her off at the hospital. She died nearby. It’s not clear whether a worker from Anishinaabe Abinoojii Family Services was with her at the hospital before she walked away into the woods. She was gone two days before a First Nations search team found her.

The man who discovered Azraya said she appeared to have died by suicide, but her family says they have not received a copy of her autopsy report.

Azraya’s family and friends have been pushing for an inquest. In July, the provincial coroner’s office told CBC News that its investigation was complete but that its reports would not be made public and that there would be no inquest. This was news to Azraya’s family.

A week later, when CBC asked why the family had not been informed of the decision, the coroner’s office had a new answer: Azraya’s case would be reviewed by an internal inquest advisory committee in September.

In the vacuum created by this lack of answers, Azraya’s parents are left to ponder the theory that their daughter died by suicide.

If that is the case, there are questions her father, Marlin Kokopenace, wants answered. Did someone give her drugs or alcohol that contributed to her despair — and if so, are they culpable in her death? If Azraya was suicidal the night she disappeared, how did police and hospital staff miss the signs and let her walk away?

And, critically, why couldn’t police find Azraya, when she was discovered just across the road from where they’d dropped her off?

Tragedy runs deep in Azraya’s family, and police have typically had some involvement in it. Azraya’s grandmother, Mary Eliza Keewatin, died in police custody in 1999, at the age of 57. Police had picked her up for public intoxication, but may have failed to notice she’d been injured. Keewatin was held at the Kenora jail, where she went into medical distress. She was later declared dead in hospital.

Keewatin’s two sons, Elvis, 24, and Morris, 29, died in 1992 while trying to swim to shore after police took their boat, leaving them stranded on an island. The pair were believed to have been high from sniffing gas. An inquest into their deaths recommended that police have better resources and training to understand the history of Grassy Narrows First Nation and deal more appropriately with community members when they find them in distress in Kenora.

Violence and a distrust of police keep spreading. Azraya’s aunt Lorenda Kokopenace said her son Christian was stabbed in the head last October, only hours after being released from police custody. The 22-year-old was in a coma for three days. In July, Lorenda started crowdsourcing a reward for information about the attack in the belief that police were ignoring the case.

“We know the police don’t care about us,” she said.

CBC News filed a freedom of information request to the Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services to get more details about Azraya’s case. It was denied, on the basis that it might interfere with a law enforcement matter, that it could facilitate the commission of an unlawful act and that the personal information in the case was highly sensitive.

A spokesperson for Ontario Provincial Police told CBC News that no internal investigations have resulted from any officer's conduct involving Azraya, but wouldn't say if the teen was in custody on the night she disappeared.

It's a critical point, because any death in custody in Ontario results in a mandatory inquest.

On the anniversary of Azraya’s death, the Lake of the Woods District Hospital issued a statement expressing condolences, but like police, officials there refused to answer any questions about what happened the night she walked away from the facility. Anishinaabe Abinoojii Family Services, the First Nations child welfare agency that was involved with Azraya, is similarly silent.

Frustrated by the silence, the young people at Grassy Narrows are turning to music to raise awareness about Azraya’s death. Led by Darwin Fobister, they hope to release a music video on social media this fall that will pressure Ontario to take action.

“Ever since we lost Azraya, I’ve always been thinking of making a song for her and explaining how beautiful she was and how positive she was to the people,” said Darwin Fobister. “She meant so much to this whole reserve. We just want something done and to move forward.”

The song, which is yet unnamed, leans more toward contemporary dance music than traditional Anishinaabe drum songs. Young women sing an ethereal chorus over an electronic beat while Darwin and other young men rap verses with uplifting messages such as “The more youth voices, the stronger we can be / Come together in strength and unity.”

Darwin hopes his work on the video will not only rally support but also help him grow into a career producing music. He plans to go to college and return to Grassy Narrows to help other young people express themselves in song.

It’s a dream his grandfather supports, even as he contemplates the fact that his grandson’s future will be tainted by mercury.

“He’ll never be normal,” said Steve Fobister. “He might just end up being like me, not being able to walk and not being able to provide for myself the daily routine it requires to be normal. It’s a depressing feeling.”

Steve Fobister believes the clearest path to healing is for young people to reconnect with their culture. He said they need to understand that as Anishinaabe, they have a deep relationship with the land, and that “when we talk about the environment, we are the environment. We are the caretakers.”

“When the land is exploited by industrial development, they are killing our medicines. They are killing us,” said the tired veteran of so many battles. “We’re trying to fight and we’re trying to save the land because that’s who we are.”

Steve Fobister said he tries to impart his traditional knowledge and Anishinaabe worldview in his conversations with Darwin. “I have so much to share. I hope more of the young people would do the same.”

Chayna Loon said she found a deeper connection to her heritage in April when she took part in traditional Anishinaabe healing ceremonies on the same weekend as the anniversary of Azraya’s death.

“I feel like the ceremonies heal us and me, especially,” she said. “I felt like I was needed there. I actually felt wanted. I felt happy being there but at the same time I was crying so bad because I just felt so overwhelmed and I just needed to let go of everything.”

Traditional healers were invited to the community by Judy DaSilva, a 55-year-old grandmother whose mercury-related mobility issues sometimes require her to use a wheelchair. Despite her disability, DaSilva has helped maintain the 15-year-old blockade against logging on traditional territory.

“Environmental racism has to stop,” DaSilva said. “We are not expendable and we are important to the world and our children have to feel that.” She said teenagers in Grassy Narrows today were “just babies when we started the blockade, but they heard the message.”

While Judy DaSilva and Steve Fobister fought mainly for environmental justice, the battle for the next generation is largely about social justice. Azraya’s friends say it starts with winning the fight for an inquest into her death, which would prove the life of a teenager from Grassy Narrows has value.

That, in turn, would give meaning to their own struggles.

“I’ve been in really dark places,” said Kyra Sinclair, “and I don’t want our younger generations to ever feel like that.”

Text by Jody Porter